Great People

VESELIN ČAJKANOVIĆ (1881–1946), CLASSICAL PHILOLOGIST AND EXPERT IN ANCIENT SERBIAN RELIGION

To Mythical Heights

He earned his doctorate degree in Munich, on ancient proverbs, was a supreme translator of Greek and Roman authors, gave the most valuable contributions by shedding light on the depths of old Serbian religion and mythology. He showed how they still pulsate in the golden Serbian path of St. Sava. Great scientist and human, awarded with the Legion of Honor and Order of the White Eagle in World War I, wounded in the defense of Belgrade, removed from the University and public life in 1945, after a fabricated indictment of the communist authorities. He ended his life disappointed and hungry, selling his books and household furnishings. In the new age, he got a street in the suburbs, but his house was demolished and his grave devastated. What about us? How far do we expect to go with so much sins against the best sons of this country?

By: Mihajlo Vitezović

”I’m a spirit, who returned to Pushkin’s Street because of unsettled depts. I stand in front of my house and look at it being torn down.”

”I’m a spirit, who returned to Pushkin’s Street because of unsettled depts. I stand in front of my house and look at it being torn down.”

These are the words of Veselin Čajkanović, in Laura Barna’s novel Fall of the Piano, while he watches from the other side the last moments of the building in which he spent most of his life. The demolishing of his house was the last chapter in the story of rises and falls of one of the most important classical philologers, researcher of Serbian religion and mythology and Belgrade University professor.

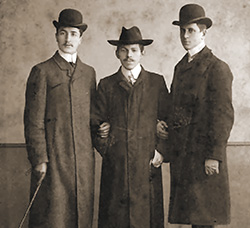

He was born on April 10, 1881 in Belgrade, as the second of six children of Nikola Čajkanović and Ana Lazić. Father Nikola was from Sarajevo, but, as a fighter against Turkish rule in Bosnia, he had to flee to Serbia. After completing the First Belgrade Gymnasium, young Veselin began studying classical philology at the Great School and graduated already in 1903. By incredible chance, just as he was picking up his diploma, he came upon Professor Pavle Popović on the stairway of Kapetan Miša’s edifice, who remembered him from his graduation exam. Hearing that Čajkanović graduated classical philology and that he wants to continue in that direction, Popović intervened for him to get a scholarship for further education in Germany. So he continued his studies in Leipzig and later in Munich, where he earned his doctorate degree on ancient proverbs.

This period was crucial for his forming and scientific development, when two directions of interest separated: classical sciences and old Serbian religion and mythology.

Ever since his gymnasium days, he was attracted by Ancient Greek and Latin. As an excellent expert in language, he translated both Hellenic (Heron) and Roman authors (Plautus, Tacitus, Virgilio, Horatius, Suetonius and others). He knew Latin so well that, besides translating, he wrote some of his bigger works in this language.

While working on the book About Zenobius’ Collection of Proverbs and Its Sources, Čajkanović was intrigued by national beliefs, so he started studying the field he will become most famous for – old Serbian mythology.

While working on the book About Zenobius’ Collection of Proverbs and Its Sources, Čajkanović was intrigued by national beliefs, so he started studying the field he will become most famous for – old Serbian mythology.

In his research, he went furthest in studying the old pagan religion, using linguistic analyses, folklore and folk literature, and comparative mythology. As Vojislav Đurić states, there are no ”results with more far-reaching significance” than Čajkanović’s conclusion that even the most popular holidays (Christmas, patron saint day), customs (godfather, hospitality), rituals (wedding, funeral) originate from the pagan system which merged with the Christian.

Furthermore, he determined that the functions of many gods were transferred to Christian saints (St. Sava, St. John, St. George), as well as historical heroes and characters (Miloš Obilić, Marko Kraljević, Stevan the High). While studying Serbian customs, he discovered influences not only of paganism and Christianity, but also much older religious systems, such as preanimism, animism and totemism, preserved in folk religion for centuries.

It’s often said that today people have, at least superficially, better knowledge of ancient or Nordic mythology than the Slavic. However, searching for old myths is a much more difficult assignment that it might seem, which Čajkanović also confronted:

”The Serbian nation wasn’t lucky to have old historians interested in its religion. It doesn’t have its Tacitus or Caesar. In order to reconstruct our former religion, we must use folk sayings and proverbs from the recent past, and folk customs. It should be, however, emphasized that our people have preserved and cherished their tradition and that its songs, stories, fairytales, proverbs, are abundant with valuable ancient material [...] This way, many beliefs and phenomena, which history missed to note, can be constructed.”

These findings, as well as setting foundations for a systematic research, will be very valuable for interpreting ancient Serbian mythology.

WHITE EAGLE FROM THE PATHS OF HONOR

After returning to Belgrade in 1908, Veselin became associate professor for Latin language at the Faculty of Philosophy. However, he had to leave his career aside when the fogs of war reached the Balkans. As a reserve officer, he fought in battles in the wars against Turkey, then Bulgaria, and immediately afterwards, while the rifles were still hot, in the biggest war conflict the world had ever seen.

After returning to Belgrade in 1908, Veselin became associate professor for Latin language at the Faculty of Philosophy. However, he had to leave his career aside when the fogs of war reached the Balkans. As a reserve officer, he fought in battles in the wars against Turkey, then Bulgaria, and immediately afterwards, while the rifles were still hot, in the biggest war conflict the world had ever seen.

”I participated in all wars as a reserve officer and first commanded a platoon, then troop and finally battalion, in all the battles in which the VII Regiment of the First Call took part” – sums up Čajkanović his military service in both Balkan wars and World War I.

He was wounded during the defense of Belgrade in 1915, which will never completely heal and follow him till the end of his life. Later during the war he fell ill from stomach typhus. His fellow fighters carried him during the entire retreat over Albania in the winter of 1916. He ended up in Corfu and was then transferred to the French port of Biserta in Tunisia. ”The gathering of Serbs in Biserta was done energetically and without pause. Thus the Serbian colony quickly grew, but it was unusually colorful and heterogeneous, and it took a long time until things were brought in order. [...] There was a case of two brothers, who ‘lost contact since the beginning of the war’, and searched for one another over the newspapers, not knowing that they were next to each other, with only the wall between the ‘Far’ hospital and ‘Lambert’ army barracks separating them!”. This was only one of the anecdotes Čajkanović noted.

He became editor-in-chief of Serbian Newspaper in Corfu, and published in its appendix Entertainer some of his ethnological works (”From Serbian Folklore”, ”From Serbian Religion and Mythology”) and memoirs (”Memories from Biserta”), in which he left valuable details about the life of Serbian emigration in this city:

”There is one thing, which the Serbs who stayed in Biserta will never forget: the warm hospitality they found in Tunisia.”

He left the war with a Legion of Honor and Order of the White Eagle with Swords of the V class, and rank of lieutenant colonel – the highest rank a reserve officer could get.

FRUITS OF THE GOLDEN PERIOD

The return to Belgrade, now capital of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians, later Yugoslavia, marked the beginning of Čajkanović’s golden period.

The return to Belgrade, now capital of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croatians and Slovenians, later Yugoslavia, marked the beginning of Čajkanović’s golden period.

He was head of Higher Education Department, manager of the State Printing House, member of the University Library Construction Board and manager of its Central Reading Room. He also continued working at the faculty and was elected dean several times in a row.

”He liked his students very much and never had a specific reception time. Particularly attentive in approach, he was always ready to help and give advice”, wrote Rastislav Marić.

Vojislav Đurić, who, working as a gymnasium professor, neglected his doctorate thesis with Čajkanović as mentor, also has memories of him. He forgot about the thesis, but his mentor didn’t: ”[...] The principal asked me [...] to come to his office immediately. Interrupting a lecture was so unusual, that I thought the police was looking for me. But, there was Čajkanović sitting, laughing and mocking me. He gave me such a lecture on duty, that even Methuselah wouldn’t forget it.”

He met Ruža Živković, student of Roman languages, at the faculty and they got married in 1921. They had two children, Marija (1927) and Nikola (1928).

The work on mythology reconstruction was in full progress. ”Ever since I returned from the war, I’ve been only working on the history of ancient Serbian religion.”

Many works followed, including those about heroes, gods, demons, in human and half-human form (Blind Anđelija, Mythical Motifs in Tradition about Despot Stevan, St. Sava in Folk Tales, About Serbian Gods of Marriage, About Serbian Gods and Demons of Healing), the cult of the dead (Memorials and Poverty, The Cult of the Dead, The Ancient Serbs’ Underworld, Patron Saint), including the newborns and newlyweds in the cult of the ancestors (Mother-in-law in the Attic)… In some works, such as The Man Who Outwitted Death, he worked on the motif of a man who tricked death, which came to take him. The same motif appears in many Indo-European religions, thus Čajkanović placed folk mythology in the context of Serbian and Yugoslav, as well as world comparative mythology.

The appearance of the Luftwaffe bombardiers above Belgrade meant the beginning of the April war. As a reserve lieutenant colonel, he was supposed to be activated, but due to the brutal breakdown of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, he didn’t even get the opportunity to step into warfare.

During Nazi occupation, a German officer moved into his house in Senjak. At the Faculty, Čajkanović kept the dean’s position and managed to somehow maintain the work during occupation, but didn’t hold lectures. According to professor of Polish, Đorđe Živanović, ”the atmosphere at the Faculty is gloomy [...] and only hope in liberation shakes the lethargy.”

DEADLY SINS TOWARDS THE GREATEST ONES

In October 1944, the united forces of the partisan and Red Army units brought the long awaited liberation. However, this period meant the most painful moments for Veselin.

In October 1944, the united forces of the partisan and Red Army units brought the long awaited liberation. However, this period meant the most painful moments for Veselin.

The new, communist authorities began deleting everyone they considered opponents of the revolution. The Belgrade University Court of Honor, which evaluated the attitude of professors during occupation, brought a verdict against Veselin Čajkanović, PhD, in 1945. He was accused of holding an internal lecture to a group of friends during occupation, participating in creating a civil plan draft for preserving the University property and signing the Appeal to the Serbian Nation, with which prominent members of the society gave their support to the fight against communists and – indirectly –legitimacy to the occupational authorities.

This was, however, not correct. Čajkanović was, despite pressures, one of the rare professors who refused to sign the Appeal, which was clearly visible in the list. Regardless of that, the verdict remained unchanged and a decision was brought about his discharge and depriving him of his civil rights:

”According to the needs, the Ministry of Education of Serbia DECIDED that Veselin Čajkanović, PhD, regular professor of the Faculty of Philosophy, shall be discharged from service. Death to fascism – freedom to people!”

So, after thirty-seven years, he was discharged from the institution in which development he took part and where he spent most of his professional career. He retreated to his house and never left it again.

He kept a diary during the last four months of his life. Blacklisted, he and his family were left with almost no source of income. ”Ruža was in the city to sell some books” (April 26), ”Maruška was at Kalenić green market this morning to sell a bedsheet, but she didn’t succeed” (June 23), are only some of the writings showing what his last days looked like.

With deteriorated health and deeply disappointed, Veselin Čajkanović died in his home in Pushkin’s Street on August 6, 1946.

SHADOWS OF THE DESECRATED GRAVE

Marked as misfit, both he and his works fell into oblivion in the following period, since studying ethnological heritage wasn’t the priority of a Marxist view of the world.

Marked as misfit, both he and his works fell into oblivion in the following period, since studying ethnological heritage wasn’t the priority of a Marxist view of the world.

Things began slowly changing in the seventies, when Čajkanović’s student, now professor Vojislav Đurić, decided that his legacy cannot be left behind. He first edited the book Serbian Myth and Religion (1973), and later Dictionary of Serbian Beliefs about Plants (1985). The crucial endeavor, however, was certainly Đurić’s publication of Collected Works from Serbian Religion and Mythology in Five Books (1994),where he collected all Čajkanović’s past works.

Old Serbian Religion and Mythology appeared here for the first time. Čajkanović didn’t complete this work, but the contents and preserved chapters show that it was supposed to be his magnum opus, the grand finale of his entire work on reconstructing old religion. It is difficult to say what significance the completion of this book would have, but the parts missing are certainly a great loss for Serbian ethnology.

Following the decision of the City of Belgrade Assembly in April 2005, the Padina Street in Braća Jerković was renamed into: Veselin Čajkanović’s Street.

Based on everything, it might seem that he was rehabilitated, and that his contribution to culture has become part of public memory again. Unfortunately, two big injustices happened.

The first is the mentioned demolition of his family house in the spring of 2012, in 22, Pushkin’s Street, which inspired Laura Barna for her novel. Built according to the design of architect Dujam Granić, following Veselin’s wishes, it was a valuable example of old Senjak architecture. Instead of being torn down, it could have been turned into a memorial house or museum.

The first is the mentioned demolition of his family house in the spring of 2012, in 22, Pushkin’s Street, which inspired Laura Barna for her novel. Built according to the design of architect Dujam Granić, following Veselin’s wishes, it was a valuable example of old Senjak architecture. Instead of being torn down, it could have been turned into a memorial house or museum.

While this was at least noticed in public, the other injustice wasn’t. The Čajkanović family tomb in Novo Groblje cemetery got a new owner, who never knew or cared about those laying there. He pulled down the tombs and poured the bones he found there – without naming and labeling them – into a common ossuary. So, the tomb of the Čajkanović family is now unknown. Veselin’s grandson resisted and attempted to prevent it, but with no success.

While writing about the Serbian cult of the dead and the belief that, if someone’s earthly remains don’t have peace, the deceased’s soul won’t have it either, professor Čajkanović certainly couldn’t even anticipate what will happen with his grave.

Čajkanović was involved in history, both ancient and Serbian, but he was also pioneer in many other fields, especially promotion of education. He faced two directions – the past and the future.

All we can do is believe that his pioneer spirit managed to, just like the character from the myth, outwit death, and that he will continue offering inspiration. Because, without a relation to the past, it is questionable how we can face the future.

***

Dictionary and Printing House

It’s unbelievable that Čajkanović didn’t abandon his scientific work during the war. On the contrary. He first published the French-Serbian dictionary with his colleague Albert Ofaux, then a grammar, lexicon and conversation guide, which served for communication between Serbian and allied soldiers.

He and Ofaux also initiated a Printing House of Serbian invalids. ”The purpose of the printing house was to teach Serbian war invalids the printing craft and to publish and distribute useful Serbian books for free”, stated Čajkanović.

***

Dabog

The most important Čajkanović’s work between the two world wars is certainly ”About the Supreme Serbian God” from 1941, where he daringly started to reconstruct attributes and functions of god Dabog. However, in the shadow of the new world war, the publication passed unnoticed.